Recent US Policies and their Likely Implications for the ECCU

by Nalissa Marieatte and Beverley Labadie

Key Messages

- The Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) has maintained significant trade and diplomatic cooperation with the United States of America (US) over the years. Inevitably, developments in the US are expected to filter down to the economies of the ECCU, through various channels, given the interconnectedness of the regions.

- Economically, the Eastern Caribbean (EC) dollar is pegged to the US dollar. This means that changes in the value of the US dollar, relative to other currencies, will affect the purchasing power of the EC dollar.

- While the region continues to value the relationship with its US neighbour, ECCU governments need to seize new opportunities that are focused on advancing the economic and social interests of regional citizens.

Introduction

The installation of a new administration in the United States (US) in January 2025 ushered in significant policy shifts pertaining to major aspects of the US economy. The new administration has been focusing on an “America First” policy agenda. This posture, initially framed by President Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the US, espouses American patriotism, protectionist trade policies and a mostly hands-off approach to international relations. In line with this ideology, the new administration outlined a plan intended to secure and protect US borders and communities, protect American businesses, level the playing field on trade and unleash US economic dominance.

Undoubtedly, the shifts in policy will have significant impacts on the US domestic economy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in its July 2025 World Economic Outlook Update, estimated that the sum total of the policy shifts would result in overall downside risks for the global economy (IMF, July 2025). By its October release of the World Economic Outlook, the IMF had revised its growth forecast for the US for 2025 downwards to 2.0 per cent, from its January Update projection of 2.7 per cent (IMF, October 2025; IMF, January 2025).

As the largest economy in the world (with an estimated GDP of US$30 trillion at the end of 2024), the US’s policy changes are expected to have far-reaching effects. The ECCU is no exception. Changing dynamics in the US economy are expected to impact the ECCU, as small open economies in close proximity to the US. Growth projections for the ECCU, often linked to developments in the US, are 3.3 per cent for 2025 and 3.1 per cent for 2026.

A Historical Context

The ECCU has had a long history of trade and diplomatic cooperation with the US. Since the region’s abandonment of the peg to the pound sterling in 1976, the Eastern Caribbean dollar (EC$) has been pegged to the US dollar (US$), steady, at a rate of EC$2.7 to US$1. The peg, which has allowed the EC dollar to be among the strongest currencies in the Caribbean today, affords stability and a relatively high purchasing power for citizens of the ECCU.

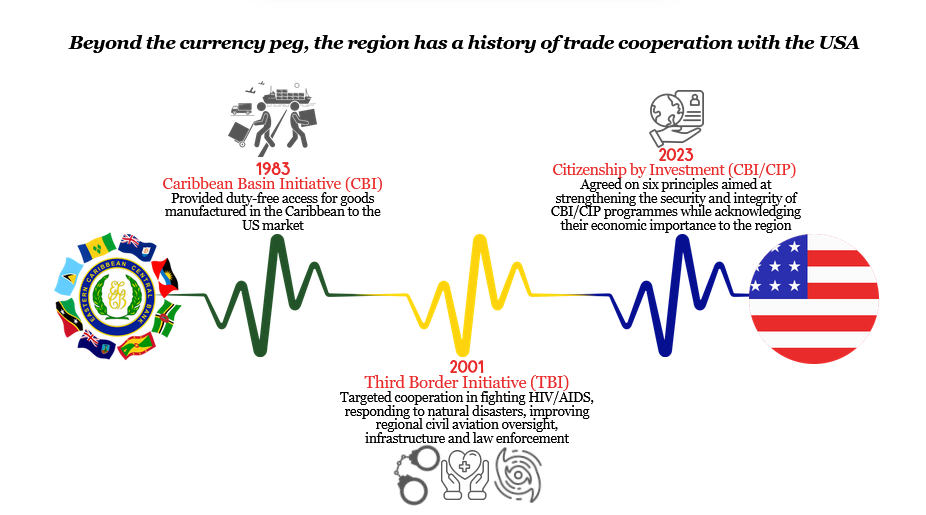

In addition, US-Caribbean relations were strengthened through programmes such as the Caribbean Basin Initiative (CBI) and the Third Border Initiative (TBI). The CBI, first formalised in 1983 through the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act, was later expanded in 2000, through the US-Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA). The CBTPA gave most categories of goods from the Caribbean duty-free entry into the US. It was due to expire in September 2030. The Third Border Initiative, introduced in 2001, intended to strengthen US-Caribbean cooperation in the areas of combating the trafficking of narcotics, youth justice, education, business resilience and health. More recently, US-ECCU diplomatic cooperation focused on the region’s Citizenship by Investment Programmes.

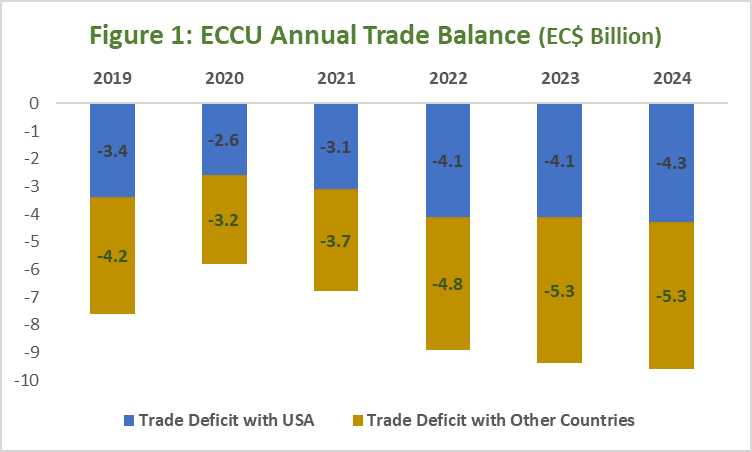

ECCU’s trade with the US has been on an upward trajectory.

The US has been the region’s largest trading partner throughout post-colonial history. This trading relationship has consistently grown both in the variety of merchandize entering our shores from the US and the value of our foreign reserves used to pay for these commodities. At the end of 2024, the ECCU’s trade deficit with the US widened to EC$4.3 billion, from EC$3.4 billion in 2019. On average, about 45 per cent of the region’s trade deficit (2019-2024) resulted from its transactions with the US (figure 1). A significant share of these imports consists of food items, with meat, cereals, fruits, vegetables, and dairy products making up the largest portion.

The US policy shifts will affect the Caribbean region, particularly the ECCU, in a number of ways. These include:

- Shifting Purchasing Power

If the value of the US dollar strengthens or weakens against other major currencies, the fixed peg of EC$ 2.7 to US$1 remains intact in nominal terms. However, the purchasing power of the EC dollar, relative to other currencies, will strengthen or weaken, commensurate with the fluctuations of the US dollar. A fluctuating purchasing power of the EC dollar will directly affect cost of living for consumers. When the EC dollar weakens, online purchases and imported goods such as food, fuel and household items become more expensive. Conversely, if the EC dollar strengthens, imports become cheaper, easing living costs. Overall, changes in the EC dollar’s value influence inflation, household spending and economic conditions in the region.

2. Pressures from Import Tariffs

Across-the-board tariffs on imports to the US have increased international trade pressures. Some countries have chosen to retaliate, beginning a trade war, which will not only influence commodity prices—including electronics, building materials, metals and pharmaceuticals—but could ultimately reshape global trade patterns. Since the largest proportion of ECCU imports comes from the US, higher prices for goods from the US market will apply upward pressure on the regional import bill through the inflation mechanism. Food is likely to be impacted significantly. The Caribbean imports between 60 and 80 per cent (FAO, 2025) of its basic foodstuff—most of which comes from the US. Equally important is that, for commodities not originating from the US, US ports act as a transit point to most of the region’s international imports.

Furthermore, the 10 per cent tariff imposed on goods originating from the ECCU to the US is likely to affect our competitiveness, as these commodities become more expensive. Nutmeg export, for example, which is very important to the Grenadian economy, could be less competitive in the US market, resulting in lower revenues and an adverse impact on the livelihood of local nutmeg farmers. As prices increase, markets may respond through lower demand for our products, which will further widen the trade deficit. The Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda, in an interview following the Development Bank of Latin America and the Caribbean’s (CAF) first international economic forum in January 2025, described the tariffs as the “largest threat” to the region (Antigua News Room, 2025).

Given the interconnectedness of the economic sectors, the Central Bank remains vigilant about likely spillover of these tariff impacts on the financial system. According to Asaju and Hinge (2025), central banks rated higher tariffs as a significant risk to financial stability, second only to cyber-attacks. Higher tariffs can drive up inflation, depress private sector profits, and increase the risk of loan defaults—particularly for businesses heavily exposed to international trade. They can also trigger financial market instability, as uncertainty around trade policies can lead to capital flight, tighter credit conditions, and higher cost of borrowing, especially for countries with weaker credit profiles. While size is a determinant of the extent of the impact, it is prudent for the Central Bank to stay on guard to these risks.

3. Strained Diplomatic Relations

Previous US administrations underscored that events in the region could have direct impacts on the homeland security of the United States and from this stemmed diplomatic initiatives characterised by bilateral and regional cooperation. The US’s more strained relations with some of the region’s other significant partners can have negative spillover effects, particularly for public health, education and supply chain-related economic activity. The breakdown in diplomatic relations can adversely influence cooperation that is critical to socio-economic development in the region. It is, therefore, imperative that negotiations attempt to preserve these relationships as far as possible.

4. Reconfiguration of Aid to the Region through USAID, WHO, UN

The US government’s foreign policy reforms led to a closure of the Agency for International Development (USAID), although some of its functions were moved to the State Department. In addition, transfers of resources to some international organisations were paused indefinitely.

The ECCU has already seen a reduction in development aid. We have seen layoffs and funding gaps created for health and social services across the region. USAID-funded programmes for persons living with HIV/AIDS, youth juvenile justice and climate resilience have been left in abeyance. Governments and institutions are scrambling to fill the funding gaps left behind.

5. Remittance Tax (Tax on Love)

The One Big Beautiful Act, signed into US law on 4 July 2025, introduced a 1 per cent levy on remittances sent from the US to Caribbean countries, effective from 31 December 2025. Experts estimate that for every 1 per cent increase in remittance cost, remittance value drops by around 1.6 per cent (Ahmed et al., 2021). Preliminary calculations suggest that this could redound to an approximately US$2.36[i] million reduction in remittances to the ECCU annually—having the greatest impact on Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada and Saint Lucia.

6. Tightening Border Controls

We have also seen the introduction of new immigration and visa policies, not only creating steep financial barriers for Caribbean nationals to enter the US but also having social implications. Higher non-immigrant visa costs, with the introduction of a new integrity fee, will strain traditional family ties with relatives in the US. The new policies have also disrupted academic plans for Caribbean students with the embassy halting new student visa appointments, pending expanded screening and vetting requirements.

The likely execution of more deportation warrants may have socio-economic effects. Some countries already face challenges with their labour markets and social infrastructure, and do not have the capacity to absorb criminal deportees or to reintegrate deportees into the society. Deportation must follow a well-managed and dignified approach to alleviate unnecessary pressures for the region.

The policy shift has also targeted the Citizenship by Investment Programmes, which play a pivotal role in the fiscal operations of governments. These programmes provide a legitimate service and fund vital infrastructural and development projects for building climate resilience. The ECCU governments have moved to enact legislation to establish a regional regulator for these programmes, as they remain valuable to the survival of our small vulnerable economies.

The Changing Policy Landscape Presents Opportunities and a Call to Action

Conclusion: Call for Action

Paul Romer said, “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.” This ‘crisis of sorts’ has presented opportunities to implement reforms that are long overdue or moving too slowly. Notwithstanding the challenges, the region must act. This action includes:

- Strengthening regional resilience by diversifying supply chains and collaborating to diversify logistics hubs. Our heavy reliance on US ports, especially Miami, subjects transshipped goods to and from the Caribbean to high tariffs and other geopolitical shocks. Building resilience requires that we invest in port infrastructure to develop regional logistics hubs. Governor Timothy N.J. Antoine, at the IMF/World Bank Spring meetings in 2025, suggested Jamaica, the Dominican Republic and Panama as potential hubs. This is perhaps on the basis of their strategic geographic locations, already existing infrastructure and connectivity of their ports.

- Securing our food supply, through sustainable food and nutrition security strategies, is imperative. Additionally, we have set goals to significantly lower our food import bill and conserve our foreign reserves. The region can only achieve these goals if we re-think our current consumption patterns and develop product-specific strategies and policies to diversify imports and import substitutes.

- Initiating and strengthening bilateral talks with new partners to co-operate on cross-cutting issues. These issues include climate change, health, digital transformation, security and trade. The Caribbean must also strengthen cooperation among ourselves and recognise the strategic comparative advantage of each Caribbean economy that would allow us to trade more amongst ourselves.

- Enhancing financial literacy and economic empowerment is critical for building resilience against shocks in the Caribbean, where many households depend heavily on funds sent from abroad. By equipping individuals with the knowledge to manage money wisely, invest in local opportunities and build savings, communities become less vulnerable to external financial disruptions such as job losses or economic downturns in migrant-host countries. Furthermore, fostering entrepreneurship and creating access to local financial resources can generate sustainable livelihoods, reducing the pressure to migrate for economic reasons. As a result, more Caribbean nationals may choose to remain in the region, contributing to local development and strengthening economic self-reliance.

The potential impact of evolving US policies on the ECCU is significant. Adapting to these shifts requires foresight and innovation. Above all, it is clear that the ECCU must come together to build a path towards resilience.

References:

Ahmed, Junaid; Mughal, Mazhar; Martínez‑Zarzoso, Inmaculada. “Sending Money Home: Transaction Cost and Remittances to Developing Countries.” The World Economy, vol. 44, no. 8, 2021, pp. 2433–2459.

Antigua News Room, (2025, February 01). Retrieved from https://antiguanewsroom.com/pm-browne-trumps-proposed-tariffs-are-largest-threat-to-the-region/

Asaju, T., & Hinge, D. (2025, August 28). Financial stability benchmarks 2025 report – The threat from tariffs.Central Banking. https://www.centralbanking.com/benchmarking/financial-stability/7973574/financial-stability-benchmarks-2025-report-%E2%80%93-the-threat-from-tariffs.

International Monetary Fund. (January 2025). World Economic Outlook Update. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/01/17/world-economic-outlook-update-january-2025.

International Monetary Fund. (July 2025). World Economic Outlook Update. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/07/29/world-economic-outlook-update-july-2025.

International Monetary Fund. (October 2025). World Economic Outlook. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/10/14/world-economic-outlook-october-2025.

UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (2025). Food Security Portal. Retrieved from: https://www.foodsecurityportal.org/node/2505.

WE WOULD LIKE TO HEAR FROM YOU!

We value your thoughts! To help us make this blog series even better, we’ve put together a very short survey—just five quick questions. Your feedback will help us create more content that’s relevant, engaging, and useful to you. It will take no more than two minutes. Click here to access the survey. Thank you for being part of our community!

About the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) was established in October 1983. The ECCB is the Monetary Authority for: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, the Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Christopher (St Kitts) and Nevis, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

Disclaimer

The ECCB strongly supports academic freedom and encourages such activity among its employees. Notwithstanding, the views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors. The ECCB may not necessarily endorse the writers’ position or guarantee technical accuracy. Readers are free to submit their comments or questions on the information presented in this publication.

[i] Preliminary ECCB Staff Calculations